Topic(s) addressed

The “Student Voices” project aimed at finding new approaches in the approach and teaching of science subjects through open dialogue between teachers and students, which was meant to allow students a voice in their own learning. A fresh and innovating approach, this project aimed to add new dimensions to the teaching profession, with its goals being to empower school systems, and develop new learning and teaching approaches through open and innovative dialogue and the use of methodologies suited to the new generation. This was to result in the adaptation of new methods by teachers, and increased involvement by students in their studies and responsibilities as learners. In line with EITA’s objectives of identifying and promoting outstanding teaching and learning practices and the fostering of mutual learning, this project also aimed to increase visibility on the work carried out by teachers and schools, while emphasising the value of E+ programmes to collaboration among European teachers.

Target groups

There were a total of 5 organisations from 3 countries that participated in the project –the municipality of Reykjavík served as its coordinator, with 4 secondary and upper secondary schools from Iceland, Denmark, and Finland as partners. Furthermore, although the UK was the project’s sixth partner, it withdrew its participation during the project’s early stages; this however had little impact on the ability of remaining partners to complete the project successfully and positively. Although there were no children who were directly involved in the project (i.e. no student mobility), students were greatly involved in school activities and the development of intellectual outputs. This applied to both students who were directly involved in classes designed for this particular project, as well as students from other classes who were being taught by participating teachers. Another target group was teachers, who were targeted both directly and indirectly (with indirect participation taking place particularly in Iceland). Outside experts and consultants were directly involved, and all participating teachers who attended meetings at other schools and/or countries were given the opportunity to listen to external experts – which was an added bonus. Participants in multiplier events and the final conference included vice principals, other teachers, psychologists, student counsellors, parents of current and prospective students, trainee teachers from the University of Iceland, and prospective students. Additionally, there was also the project’s general audience from its Facebook page and its official website. All project partners had some experience in international cooperation, although they had yet to work as a team. Schools were chosen as participants based on their secondary and upper secondary merits, with a focus on innovative practices – especially with regard to ongoing changes and adjustments in national and European education systems.

Methodologies

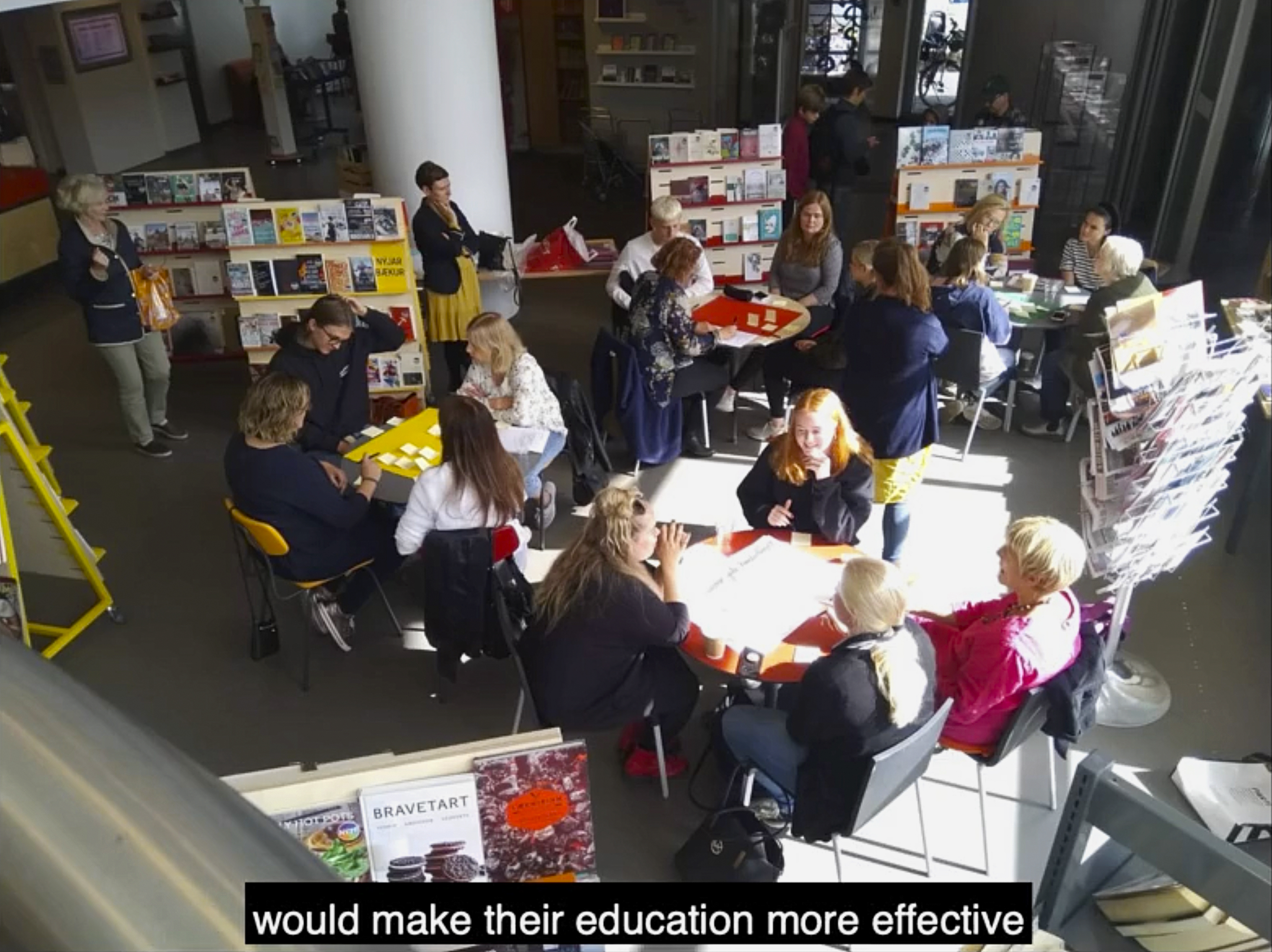

The project was both innovative in its approach to construct open dialogue and its involvement of students and teachers. Furthermore, it focused on working with available structures in the development of educational systems by concentrating primarily on mathematics and science education, although there some focus was also made on language learning. Part of the project was to examine the education system and curricula of each country, and define best practices from each country that could perhaps be promoted and transferred to other schools and countries. The project’s innovative approach was the dialogue among experts, teachers, and students, with a focus on student involvement in the design, development, and testing of various approaches to learning and teaching, as well as methods that enhance students’ active participation in activities. Among participating organisations, were professionals with experiences in teaching, counselling, research, and development, as well as students with unlimited imaginations and perspectives on a digital future. The project’s aim was to create a process where such perspectives and roles were integrated, with teachers listening to and absorbing ideas from students.

Environments

The project was aimed primarily at secondary and upper secondary schools from the 3 participating countries and coordinated by the municipality. The organisation in question was a service centre operating under the City of Reykjavík that was responsible for providing professional support to schools in relation to welfare and family issues, students with special needs, as well as being a platform for cooperation among different schools within their respective neighbourhoods, and serving an advisory role to schools, parents, and students. Icelandic schools were arguably the main contributors to the project’s actual design, ideation, the initial operation of workshops, and the organising of multiplier events and the final conference. Following their attendance of the workshops, other schools implemented the project’s practices into their own organisations, and provided coordinators with strong feedbacks. The schools also organised several Transnational Project Meetings in order to learn as much as possible from each other. Communication lines were quite open between all participants, with all their work published on the project’s publicly-accessible website.

Teachers

This project both directly and indirectly involved teachers; teachers who were directly involved were mostly those who taught science subjects and language teachers, with both groups strongly encouraged to involve other teachers from their schools in their findings. As a whole, the group benefitted from the fact that one of the project’s key elements was the active listening and democratic process, which in turn set the tone for cooperation between partners and institutions. The project’s democratic methods were widely used in the work carried out by groups outside of the partnership. Such an environment of peer learning both between participating institutions and between teachers and their students, was a very positive element with regard to the project’s cooperative processes. The atmosphere was one of trust and positivity, with a focus on the work to be implemented. Students responded well to the opportunity to speak up and the increased responsibilities they were given in their education processes. For teachers, this approach focused on the role of the teacher as a mentor and a coach who assisted students both in finding their own way to learn and the definition and demonstration of their learning styles to others. On the whole, using active dialogue as a key component to increase students’ responsibility for their education processes was thought to be very successful by teachers, but also challenging to implement. This was in line with the prediction of external experts and teachers who benefitted from shared troubleshooting experiences during transnational meetings.

Impact

The acquisition of new skills and competences came from implementing intellectual outputs at each stage of the project, as well as from the teaching workshops that were held at all transnational meetings (following the kick-off meeting). At the local level, the project’s activities strengthened school culture and quality of teaching; enhanced student involvement and responsibility for their own education (as well as their understanding of the principles and aims of general mandatory education); and, strengthened the role of teachers in developing innovative and successful ways to learning and teaching. The desired impact at the regional and national levels was that for participating schools and communities, the emphasis on student voices, teaching and learning methodologies, and the focus on “best practices,” were shown to work, and could potentially be employed in other schools and communities in the future. Furthermore, relevant stakeholders had the opportunity to widen their horizons and gain a better understanding of the EU’s education systems, their diversity, transferable knowledge, and best practices, all of which may contribute to the lobbying process for education policies and processes that are more focused. The project’s impact at the international level was networking processes with other schools, regions, and countries, with the information gathered from such networking relationships used to improve the design of local education policies. Lastly, project partners hope to encourage the interest of schools and communities outside of the consortium towards successfully employing the project’s outcomes.

- Reference

- 2017-1-IS01-KA201-026537

- Project locations

- Iceland

- Project category

- Secondary education

- Project year

- 2021

Stakeholders

Participants

Ingrid Jespersens Gymnasieskole

- Address

- Denmark

Kvennaskólinn í Reykjavík

- Address

- Iceland

Landakotsskóli

- Address

- Iceland

Munkkiniemen yhteiskoulu

- Address

- Finland